Keepers of the dead

Keepers of the deadLogan Square couple's museum of mourning collects photographic funeral artifacts

By Robert K. Elder (relder@tribune.com)

Tribune reporter

January 17, 2008

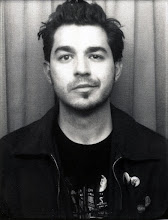

Anthony Vizzari sees dead people. In antique stores, on eBay -- in his living room. A whole museum of them. That's because Vizzari, with the help of wife, Andrea, collects photographs of the deceased. Their Museum of Mourning Photography & Memorial Practice, a small but growing collection (about 1,050 pieces), occupies part of the Vizzaris' Logan Square apartment.

"It should not be about morbid fascination. It's about human ritual," says Anthony Vizzari, 27, an architect and photographer by training, a pack rat archivist by instinct.Mourning photography dates back to the foundations of photography in the 1800s. What may seem morbid today was a well-established memorial custom in the 19th Century. When a loved one passed away, formal death portraits were taken, preserved, even displayed in homes. Smaller portraits were sent to family members unable to attend the funeral. The practice especially extended to the funerals of young children and stillborn babies as a way to incorporate them into family history.

"Mourning goes all the way back to the beginning of time, and this [collection] is one more way of looking at it," says Vizzari.

And look at it he does, every morning, when he has coffee. Or watches a movie with his wife. Or even just enters their apartment. An alcove in his living room hosts an entire wall of the dead, photographed as they lie -- seemingly asleep. The images are mounted in lovingly crafted, ornate frames. Some carry ribbons or montages that read: "Gone But Not Forgotten."

The 3-year-old museum is open to the public, by appointment only, though with friend and curator Melissa Damasauskas, 26, the Vizzaris are building a digital version of the collection online.

Of the Vizzaris, Anthony is the more serious and soft-spoken, a foil to wife Andrea, 31, who is funny, a tad saucy and prone to giggles -- especially at the oddness of their living room/museum.

When they started dating in 2001, she found her boyfriend's interest in grieving customs, "a little creepy. Especially the pictures of the children, I found to be really sad. But once I found a little bit more about the history, I could appreciate it more. I think what really brought us together was, we both had interests in collecting."

Anthony Vizzari started collecting funeral ephemera more than 11 years ago, after he picked up a box of random photographs in a Maine flea market, on a whim.

Card sparks interest

"In my first box, I found my first mourning piece -- a funeral card," he recalls. "I didn't really know what it was, but I kept finding more."Quickly, it became an obsession with a resonance that he wasn't conscious of, at first.

"For me, I think it was a personal thing," Vizzari says. "I was collecting them because I had some mourning process I was trying to go through myself, but not really understanding."But more on this in a moment.

The Vizzaris and Damasauskas make what could be mistaken for a nouveau Addams Family, dressed stylishly in black -- hair gel and makeup carrying the slightest undertone of hipster Victorian/Goth aesthetic. But this superficial impression would serve to fundamentally misunderstand them.

Actually, they are scavenging preservationists, crusaders for a lost world of loved ones whose families followed them into oblivion. Much of the collection is rescued from antique stores, estate sales, flea markets, online auctions and garage sales.

Vizzari hopes to build a repository, a monument to the discarded dead, starting in his living room. Eventually, he hopes to find a brick-and-mortar location for the collection to preserve it even after he dies.

But for now, "It's self-funded, with some donations, but we're building a digital archive project where people contribute images, information. We want it to be accessible to the public, and we're also insisting it's free."

No shock value

The Vizzaris reject gruesome items outright: crime-scene photos, videos of accidental death, a la the popular "Faces of Death" video series. In fact, that sort of material makes them squeamish. But they are seeing their funerary collection swell as newer grieving customs -- memorial or "tombstone T-shirts," YouTube tributes to fallen soldiers and commemorative Web sites -- permeate the culture."

Some of the more contemporary items are interactive," says Vizzari, which brings up a sensitive question in his own marriage.

"I asked Anthony, a long time ago, 'Are you going to take pictures me when I die?' And he said, 'Of course I am!'"Andrea Vizzari says. "But I want people to remember me, living, exuberant and alive."

"But that's what it is about," Anthony Vizzari interrupts.

"This is misinterpreted. It isn't about the dead, it's about the living."

"It's a confrontation with your own mortality," adds Damasauskas, playing the moderator. "Seeing an image of someone who has died actually helps you work through your grieving, you can't put it aside."

Which brings us back to Vizzari. After thinking about it, he remembers that the museum's first piece was not a memorial card bought in Maine, but the funeral program of a high school friend, Ryan Duffy."

We were in a car wreck; I was a passenger. He was driving and didn't survive," Vizzari says, quietly conjuring the details of the story.

Vizzari was 14, barely a freshman. Duffy was older, 17, driving too fast on a winding Connecticut back road in the rain. The car hydroplaned taking a corner, striking a telephone poll and killing Duffy. Vizzari fractured both feet and other friends in the car suffered head injuries, but they all survived.

"I lost a couple other friends in that short time period. Looking back, maybe I didn't pay them the proper respect. I didn't have my own mourning process. You're a kid, you don't know what to do," says Vizzari.

"But it really does bother you," he says. "I think these photographs became a surrogate for my mourning process, as weird as that sounds. Everyone has their own way of dealing with things. It's therapeutic, in a sense."

For more information, visit the museum online at: www.mourningphotography.com.----------http://www.mourningphotography.com.----------mailto:mourningphotography.com.----------relder@tribune.com/

IN THE WEB EDITION: Meet the museum's founders at http://www.chicagotribune.com/features/lifestyle/chi-0117mourningjan17,0,3288666,full.story .

Copyright © 2008, Chicago Tribune

2 comments:

Congratulations on this article.

Your work, what you are doing and building and sharing with the world is so very important.

This news are surprising on my part. Glad to hear it though.

arizona house cleaning

Post a Comment